Last week, we had an especially cool project, with Marco immediately suggested after we said that we were writers. (Mostly out of relief that he could begin having us write his blog posts for him). We interviewed two village elders, Ooey Khambao (age 84) and Ooey Jum Supaeng (age 77), and wrote up what the village was like when they were born and how it's changed. (Ooey is a Thai term for grandmother or elder that precedes their name.)1

So with Marco and Nok translating (and, of course, in turn fielding questions about Empress Baby Serena), we wrote a story that synthesizes their voices and their experiences. There's probably a little that we missed, but we tried to catch it all, and swear that we didn't make anything up, not even the tigers.

What we call Mae Mut now was all an enormous teak forest when we were growing up. The rice fields that you see around the farm now were just trees. There was a village here, where our parents and their parents lived, but it was tucked into the forest. Then about fifty years ago, in the 1960s, the government came to log the teak with dozens of elephants, whose descendants now live in the elephant camps along the road here. Except, the road wasn't built until thirty years ago or so. The elephants have an easy life now! Tourists are much lighter than teak logs.

The government cleared all of the teak trees, but the people had to make the fields. All of the rice terraces were cut out of the ground by hand. This area didn't really belong to anybody, so if you wanted a piece of land, all you had to do was go and clear it. The headman of the village and his family were rich to begin with, so they just bought land from everyone else. More families would come to live here, and buy a parcel of land. Only one family has ever left Mae Mut, to our knowledge. Everyone wants to stay because it’s very easy to live here, there is water and enough land for everyone. A parcel of land like your garden would have cost 4000 Baht back then [whereas today it would be 2-3 million Baht]. We would wake up at dawn, and start a fire to cook the rice and ward off the mosquitoes. Then work all day, eat at midday, and light a fire at dusk to cook and again ward off mosquitoes. At night, the dogs couldn't sleep outside because of the tigers, so they slept in the house. We lit fires at night near the livestock to scare off wild animals.

In the village itself, the houses were different depending on how wealthy your family was. Rich families would build wood houses, since they could afford handsaws. There were no chainsaws back then! Poor families built bamboo houses, which were sometimes very cold during the winter! If it was cold we would sleep in the rice house. We lived in bamboo houses when we were first married, but we persuaded our husbands to go into the forest to get us some wood.

Before the road was built, we had to walk to the market in Mae Wang, on a narrow trail through the mountains. The market was one of the places we would get news of the country, since before the radio, news spread by word of mouth, usually whenever there was a visitor from farther away. When we went to the market, everything we had brought to sell—mushrooms, bamboo shoots, foraged vegetables from the mountain, and oil wood for lighting fires—we would carry on our backs. The journey would take two days: we would leave at 8 AM, walk all day, and arrive in Mae Wang at 5 PM. After spending the night, we would sell at the market in the morning, buy rice and whatever we needed, then walk back to Mae Mut. Back then a liter of rice cost ½ Baht. Now it’s 30 Baht! We grew cotton, which we spun into thread to weave our own clothes. To color them, we would use vegetable dyes, like roselle for red. It generally took three days to make an article of clothing.

|

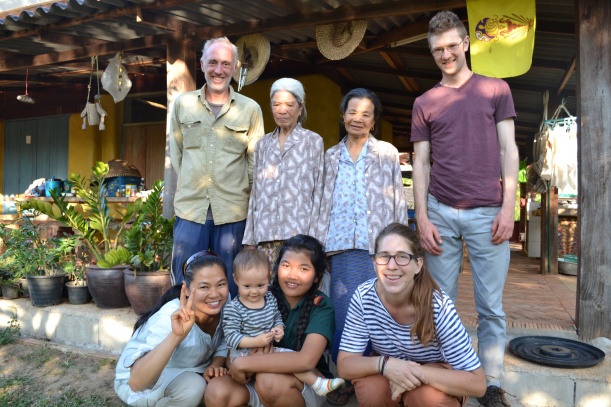

| Ooey Khambao was quick to smile. |

Farming was also different then than it is today. We also didn't really have days off; there was too much work to do. There were only Buddhist calendar holidays, when we would go to the temple, or else weddings and funerals. There were no tractors and no machines, no fertilizer or chemical pesticides. We used cow manure. Everything was done by hand or with the help of water buffalo. Sometimes, we had to buy rice, because there were no chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Less rice grew, and often it wasn't enough for the whole year. The rainy season, around June and July, was the hardest, because we would plow the rice fields. That was always hard work with the plow. If your family didn't have enough water buffalo to plow the field, you would borrow the buffalo from a neighbor. And you had to train the buffalo yourself, so that it would listen when you told it to turn or go straight. They didn't always listen!

We ate the vegetables that we grew by ourselves—eggplant, cucumber, soybean, Thai vegetables with no English names—and sold some in Mae Wang. There was fruit from surrounding trees—papaya, banana, coconut. Fish and crabs from the river, and chickens that we raised. Pigs and buffalo weren't eaten as often as chicken, and buffalo were only killed if they’d had a bad accident. In either case, the family would go around and ask everyone in the village who wanted a piece of this pig or that buffalo, and whoever wanted a portion would pay about 3 Baht for two or three kilos of meat.

When we were children we played skipping rope, or sometimes we would compete to see who could jump the highest, or bounce rocks to see who could pick up the most. And the boys would wind up rattan balls to play ball. Most children went to school for a little while, because it was free (the government paid for it), and that way the parents wouldn't have to worry about them. Until a few decades ago, the Huay Pong school (the nearest to Mae Mut) only had four grades. Few children made it all the way to fourth grade, because they were kept at home to work. Starting at 10 or so they could care for younger siblings, or at 13 start working in the rice fields. Children could go to school at any age, though they generally started at seven or eight. But maybe you had to take a few months off because you had to care for a new sister, or go into the rice field, so you would come back a year later. But once you turned fifteen, the teacher would tell you that you should go work in the rice field, you were too old for school! And once you turned fourteen or fifteen you couldn't really touch someone of the opposite gender, not even to hold hands, until you were married. So we got married young! For our weddings, we exchanged matching bracelets instead of rings, and the immediate families of the husband and wife would all have dinner together. That was it.

The Karen also used to live closer to where the village is now. The Mae Sa Pok Karen village used to be about where we are, but they moved when more families started coming into the village. There wasn’t any animosity, we were just two different cultures, and they wanted their own private space. Back then, the Karen didn't go to the school in Huay Pong, they had their own village school. Often the children were taught by soldiers, because they were up in the mountains anyway to watch out for people who were growing drugs. Once the King’s Projects began, and people were encouraged to grow tea, coffee, and vegetables instead of illegal crops, university-educated teachers began to come to the mountain school. Initially they only taught half a day, because it would take half a day to walk up and another to walk down, but later, recent graduates were sent up to teach, because they didn’t have spouses or family attachments.

This temple in Mae Mut is the oldest one in this entire area. The people from many surrounding villages came to build it, because with only a dozen or so families in the village, there were not enough people to do the job. So everyone in the area helped to build our temple, and then everyone helped to build the school in Huay Pong. Those were the first public buildings, and then followed more temples in the other villages. There also used to be many more monks. Now, there are too many distractions, and fewer people truly believe in the Buddha. Monks used to go into the mountain wilderness to meditate, entirely by themselves, but now that happens very rarely. Also, now there are more older people at the temple, there are not that many children. When we were young, children had to go to temple, because they couldn’t be left at home by themselves. It wasn’t safe—there were tigers and wild animals outside. So they were always with their parents at temple, starting very early. Now, children have more distractions, like internet, school, television, and they don’t consider their life after this one. They don’t think about death.

1 Nobody in Thailand has just one name. There's a formal name, which only appears on passports and official documents really. Then a nickname (or chêu lèk, "play name," ชื่อเล่น), which you would use every day. And finally there's a kinship term that precedes the nickname. Pii Hom's name, for instance, means Elder Sister Hom.

When we were children we played skipping rope, or sometimes we would compete to see who could jump the highest, or bounce rocks to see who could pick up the most. And the boys would wind up rattan balls to play ball. Most children went to school for a little while, because it was free (the government paid for it), and that way the parents wouldn't have to worry about them. Until a few decades ago, the Huay Pong school (the nearest to Mae Mut) only had four grades. Few children made it all the way to fourth grade, because they were kept at home to work. Starting at 10 or so they could care for younger siblings, or at 13 start working in the rice fields. Children could go to school at any age, though they generally started at seven or eight. But maybe you had to take a few months off because you had to care for a new sister, or go into the rice field, so you would come back a year later. But once you turned fifteen, the teacher would tell you that you should go work in the rice field, you were too old for school! And once you turned fourteen or fifteen you couldn't really touch someone of the opposite gender, not even to hold hands, until you were married. So we got married young! For our weddings, we exchanged matching bracelets instead of rings, and the immediate families of the husband and wife would all have dinner together. That was it.

The Karen also used to live closer to where the village is now. The Mae Sa Pok Karen village used to be about where we are, but they moved when more families started coming into the village. There wasn’t any animosity, we were just two different cultures, and they wanted their own private space. Back then, the Karen didn't go to the school in Huay Pong, they had their own village school. Often the children were taught by soldiers, because they were up in the mountains anyway to watch out for people who were growing drugs. Once the King’s Projects began, and people were encouraged to grow tea, coffee, and vegetables instead of illegal crops, university-educated teachers began to come to the mountain school. Initially they only taught half a day, because it would take half a day to walk up and another to walk down, but later, recent graduates were sent up to teach, because they didn’t have spouses or family attachments.

This temple in Mae Mut is the oldest one in this entire area. The people from many surrounding villages came to build it, because with only a dozen or so families in the village, there were not enough people to do the job. So everyone in the area helped to build our temple, and then everyone helped to build the school in Huay Pong. Those were the first public buildings, and then followed more temples in the other villages. There also used to be many more monks. Now, there are too many distractions, and fewer people truly believe in the Buddha. Monks used to go into the mountain wilderness to meditate, entirely by themselves, but now that happens very rarely. Also, now there are more older people at the temple, there are not that many children. When we were young, children had to go to temple, because they couldn’t be left at home by themselves. It wasn’t safe—there were tigers and wild animals outside. So they were always with their parents at temple, starting very early. Now, children have more distractions, like internet, school, television, and they don’t consider their life after this one. They don’t think about death.

1 Nobody in Thailand has just one name. There's a formal name, which only appears on passports and official documents really. Then a nickname (or chêu lèk, "play name," ชื่อเล่น), which you would use every day. And finally there's a kinship term that precedes the nickname. Pii Hom's name, for instance, means Elder Sister Hom.

You've captured a fabulous history of the area and the people and how life has changed over time. But, in a way, it's kinda sad. You've done them proud.

ReplyDeleteSo do you now post Marco's blog as well as your own? What's the link for his?

Who is the girl with glasses?

The girl in the glasses is Molly, who joined us for three weeks in the middle of our stay at Mae Mut. She's really great, and has all kinds of experience volunteering in places like Indonesia, India, and New Orleans, where she stuck around after Katrina to give mule-driven tours.

DeleteMarco's blog can be found at: http://maemutgarden.com/blog/

There are some duplicates, but the fruit tree post is great! Might look familiar because I am putting it up on this blog right now....

Very interesting. I'm especially intrigued by the respectful separation by the Karen from the larger community, it struck me as highly unusual. I think its very revealing how the"simple" life of the past, as it is presented at times, regardless of cultural context, always is never simple. So, are you young people thinking more about death?

ReplyDeleteWe think about death every time we cross a street full of a dozen oncoming motorcycles.

DeleteWe tried to ask more questions about the separation of the Karen, but that really seemed to be all the elders had to say about it. I honestly think it was just a matter of keeping the Karen culture separate from Thai culture. They're already a stateless people, and to further lose their children to Thai culture would be a real loss in their eyes. We spent a weekend up in the Karen village (which we will write about soon, it was our favorite excursion) and it felt like going back in time, in some respects.

Very fine. And brings to mind so very much — the enormous changes today from my own childhood on a farm, the stories of elder-friends in Haiti, etc. etc. etc. Thanks for doing these interviews!

ReplyDeleteThanks very much! Did you grow up in Haiti?

Delete(Foiled again by technology. I have no idea where the Images of Haiti tag came from. Even less idea how to change it.)

ReplyDelete